We interview Anastasia Todd about her book, Cripping Girlhood

Our member, Dr. Anastasia Todd (University of Kentucky, US), talks about her book, Cripping Girlhood (University of Michigan Press, 2024).

Q: What is this book about?

In the 2010s, the disabled girl curiously emerges across a range of different sites in the United States’ mediascape. No longer represented solely through discourses of risk, pathologization, and vulnerability, and taking drastically different forms than in Jerry Lewis Telethons or in advertising for the March of Dimes, the disabled girls that come to hypervisibly materialize in the recent cultural imaginary are pageant queens, social media influencers, and disability rights activists.

Unlike decades previous, these spectacular disabled girls are not only figures to be looked at, but to be listened to. Cripping Girlhood is interested in what happens and what it means when certain disabled girl subjects gain cultural recognition and visibility as “American girls, too,” to use the words of Melissa Shang, who in 2014 created a viral Change.org petition imploring American Girl to create a disabled doll of the year. The book asks, why disabled girls, why now?

Cripping Girlhood traces representations and self-representations of disabled girls and girlhoods across the mediascape at the beginning of the twenty-first century, spanning HBO documentaries to TikTok. Frequently, the book suggests, the figure of the exceptional disabled girl emerges at this moment in media culture as a resource to work out post-Americans with Disabilities Act and neoliberal anxieties about labor, the family, healthcare, and the precarity of the bodymind. Most importantly, the book explores how disabled girls, more than symbolic figures to be used in others’ narratives, circulate their own capacious re-envisioning of what it means to be a disabled girl.

Q: What made you write this book?

Like many academics, my intellectual interests come out of personal experience. I took a Girlhood Studies class in undergrad that really sparked my initial curiosity. At that point I didn’t think girlhood was something that you could study.

One semester later, in my first class in graduate school, we read Rosemarie Garland-Thomson. I had never encountered feminist disability studies before, and I had one of those light bulb moments where I thought about my own experiences growing up. I became very eager to write about disabled girlhood and realized that there wasn’t anything out there from a feminist disability studies perspective or a girlhood studies perspective.

In the fields where the disabled girl appears, like education and psychology, she is rigidly defined by a medicalized and gender essentialist framework, and her girlhood is understood through discourses of risk and vulnerability. Within these fields, disabled girls are presented as objects of theory, rather than subjects who theorize.

I started thinking and theorizing about disabled girlhood from a different perspective, one that centers disabled girl experiences and knowledges. Disabled girl knowledges have much to offer all of us: we can learn from how they leverage humor, how they theorize about ableism, and how they enact interdependence. My work suggests that thinking deeply about disabled girlhood offers us all greater insight into the fragile contours of humanness, of what it means and how it feels to grow up and confront and upend expectations and futures that have already been decided for you.

An excerpt from the Introduction (Cripping Post-ADA Disabled Girlhood):

In 2017 I was riding a bus in Los Angeles that was barreling down Sunset Boulevard when I came across a curious bus bench billboard. The billboard was an image of a young, white girl with Down syndrome. Her light brown hair was braided and pulled back. This drew my attention to her youthful face, painted in its entirety as an American flag. She was holding a paint brush and gazing at herself in the mirror. Is she admiring her work, I wondered? It appeared that she was in the intimate space of her bedroom. I noticed that behind her was a dresser and lamp, and next to her, hanging alongside the mirror were red, white, and blue beads and a bronze sports medal. I wondered what the image was trying to tell me. As I fumbled around in my backpack for my phone to take a picture, I took note of the hashtag hiding unobtrusively in the corner, “#WeAreAmerica.” Next to it was the phrase, “Love Has No Labels.” I felt ambivalent as I pondered my encounter with the image of the disabled girl that was at once spectacular and mundane. […]

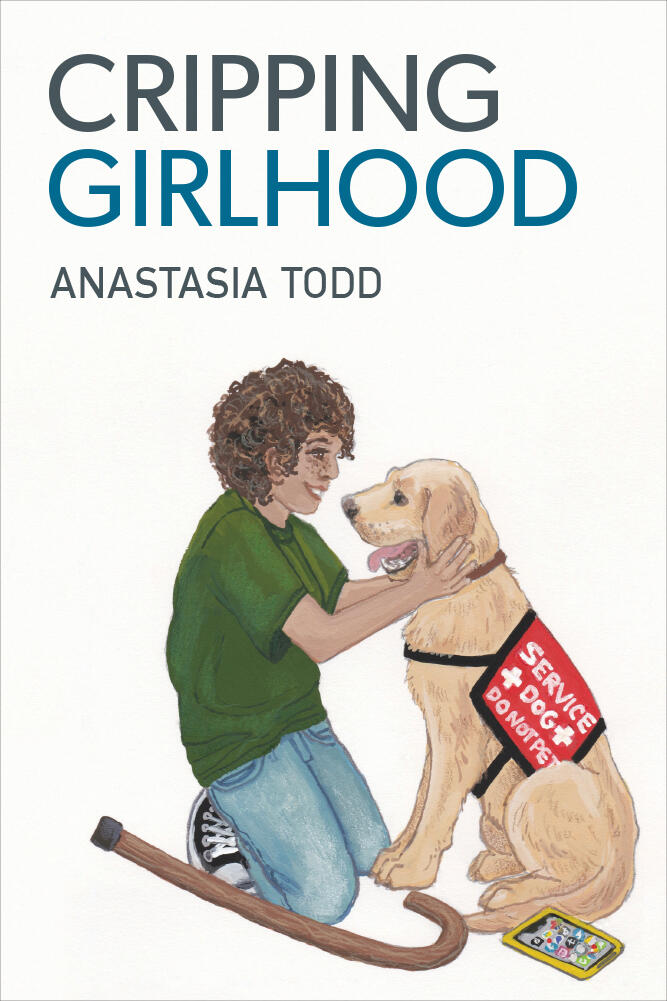

There is a temporal urgency to the critical study of disabled girls and girlhoods precisely because there has been a recent and fervent proliferation of representations and self-representations in media culture. So, in returning to my question, “Why disabled girls? Why now?,” the book contends that not only is it about time, but that the time is now. The bus bench billboard that I began this chapter with is one such site that suggests the emergence of the figure of the disabled girl has much to tell us about the contemporary moment. Cripping Girlhood uncovers how the exceptional figure of the disabled girl, although produced and circulated in various iterations—as a disabled “future girl,” an object of happiness, an online disability educator cum social media influencer, a sentimentalized testament to the rehabilitative properties of the service dog, and as a pedagogue of death—emerges in media culture at this moment to serve as a resource to work through contemporary anxieties about the family, healthcare, labor, US citizenship, and the precarity of the bodymind. These exceptional disabled girls offer lessons to the non-disabled viewer about tolerance, benevolence, and love in neoliberal, post-ADA times. Most often, representations of disabled girls who are exceptionalized, or recuperated as valuable, shore up logics of white supremacy, national exceptionalism, and, paradoxically, able-bodied supremacy. I track how the process of recuperation or exceptionalization is incredibly uneven. The disabled girls who become valuable and visible in media culture become valuable and visible because they ossify existing, normative understandings of disabled girlhood and girls: as potentially productive, as heterosexual, as potentially reproductive, as rehabilitatable, and as empowered and empowering. But, in turning to disabled girls’ self-representations, the book contends that disabled girls are actively contesting this process of ossification through charting their own meaning of what it means to be a disabled girl, as well as through imagining and building a world otherwise. It is a world where they grow “sideways” with their service dogs, dwell in stillness, claim cripness in the face of compulsory able-bodiedness/mindedness, and enact their desires, even if it makes adults uncomfortable.

Ultimately, although this is a book about representation, Cripping Girlhood is concerned with the material stakes for disabled girls caught up in the shifting politics of disability visibility. As cultural studies scholars remind us, representation matters; it is inherently connected to the “real.” Cripping Girlhood grapples with the variegated ways disabled girls are represented and represent themselves and unearths how visibility for some disabled girls does not translate into liberation for all disabled girls. The disabled girls who circulate as emblems of post-ADA progress, those who are constructed as productive, happy, and empowered, obscure how discourses of disability and girlhood collude with other systems of oppression and function as regimes of normalization, exclusion, and depoliticization.