When students log into QMplus, their experience is shaped by more than just the content. The way information is introduced, how activities are sequenced, and how assessments are explained all influence whether learners feel supported or overwhelmed. In this article, we explore why such design elements matter and how you might implement them in your online learning materials.

Building on the success of the Snippet tool, the Technology Enhanced Learning Team and the Digital Education Studio are scaling up these good practices through a wider set of design components, referred to as Components for Learning (C4L). Our aim is to give staff clearer, more consistent design options that enhance navigation, highlight key learning moments, and ultimately create a more engaging and scaffolded learning experience for students.

Why these design elements matter

These design elements signpost and highlight good learning principles. They make visible the cues, prompts, and guidance that align with effective pedagogy. By doing so, they help students recognise what matters and when.

First, C4L signal scaffolding and support. Research shows that scaffolding in online higher education produces significant gains in both cognition and metacognition (Doo, Bonk, & Heo, 2020). Elements such as step markers, workload cues, or contextual summaries flag where support is built in, helping learners feel oriented and confident.

Second, the components highlight case studies and real-world examples that draw students’ attention to opportunities for active and authentic engagement. Such elements act as powerful signals of meaning in practice. Modules based on authentic experiences promote student engagement across cognitive, relational, and behavioural domains (Young & Tullo, 2020).

Third, by signalling the presence of feedback, these design elements reinforce the social and relational dimension of learning. Feedback is widely recognised as one of the most powerful influences on student achievement and progress (Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Components like Expected Feedback draw learners’ attention to when and where feedback will be provided, reminding them that assessment is not simply a judgment but also an opportunity to learn.

Finally, they reinforce accessibility and inclusivity. A review of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) confirms that consistent layouts, multimodal cues, and clear signposting reduce barriers (Al-Azawei, Serenelli, & Lundqvist, 2016). Design elements help reinforce these inclusive practices and make the visual experience consistent, reducing cognitive load during navigation. Clear signposting, predictable layouts, and multiple representations of information help students navigate QMplus and understand its content more easily.

How we can put design components into practice

As part of the MSc Advanced Neonatal Practice, one of our CARE agenda programmes, we have begun integrating C4L to enhance the online experience. The examples below show how these design elements signal good practice and support learners in navigating complex content with clarity and purpose.

1. Tip component

This Tip component is designed to highlight an insight or idea that helps guide students in their learning. In this case, it encourages learners to see how even a focused area of neonatal practice can generate multiple research questions, prompting them to think critically about evidence-based care.

2. Quote component

This Quote component highlights authoritative, evidence-based definitions, which brings the academic or professional voice directly into the learning space. This adds authenticity, grounding the content in credible sources and making the speaker’s presence felt in the material.

3. Do/Don’t Card

The Do/Don’t Cards signal key expectations before students begin the task, outlining what to do and what to avoid. By setting boundaries and clarifying instructions, it reduces ambiguity and ensures learners approach the activity with the right mindset.

These are just a few examples of how design components can be used to enhance the visual learning experience in QMplus. Visit the components for learning webpage to see the full range of component types and explore additional user cases from across the sector.

Adding design components to QMplus

Adding new components is designed to be as straightforward as possible. They can be added to pages, books, forums or anywhere you use the text editor in QMplus.

Use the button that looks like a Lego brick in your editor (circled in green below):

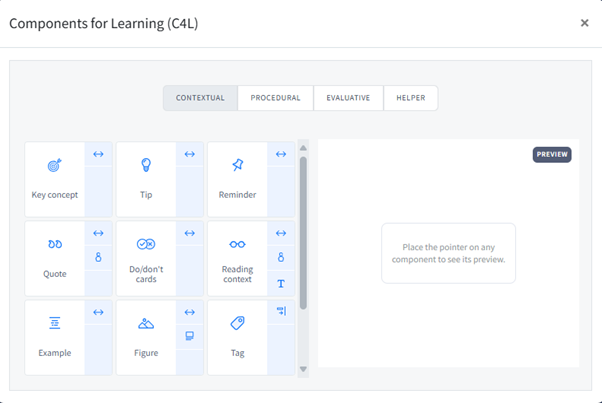

Explore the menu of components, split across four categories: Contextual, Procedural, Evaluative and Helper:

Soon there will also be a Custom tab containing banners and other elements designed by the Digital Education Studio to fit with the QMUL colour scheme. Hover over each component for a preview of what it will look like, and select the component to add it to your course wherever your cursor is.

Once added, edit the placeholder text like you would any other in QMplus.

Final thoughts

The components for learning are one of many beneficial features that have come with the recent upgrade to QMplus. They can help us develop clear and engaging QMplus sites. As always, a thoughtful approach is still required: A carefully considered use of components ensures they support rather than overwhelm, keeping the learning journey clear and focused.

To learn more about the other updates in QMplus, such as changes to assignments and the new assignments notifications, visit the TELT website.

References

Al-Azawei, A., Serenelli, F., & Lundqvist, K. (2016). Universal Design for Learning (UDL): A content analysis of peer-reviewed journal papers from 2012 to 2015. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 16(3), 39–56.

Doo, M. Y., Bonk, C., & Heo, H. (2020). A Meta‑Analysis of Scaffolding Effects in Online Learning in Higher Education. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning 21(3).

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112

Young, S., & Tullo, E. (2020). From criminology to gerontology: Case studies of experiential authenticity in higher education. Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 8(1), 127–134.