Widening access to international opportunities: a combined virtual international exchange and simulated pandemic exercise

In collaboration with

This virtual international exchange was designed to consolidate students’ learning in their respective programmes and facilitate the exchange of country-specific knowledge and experiences. Activities aimed to create a space for students to work together and develop their intercultural competence.

Introduction

We combined a virtual international exchange with a simulated pandemic in which students played the role of advisors to the World Health Organisation (WHO), working in teams to respond to a fictional pandemic as it unfolded. The activities were designed to consolidate the students’ learning in their respective programmes and facilitate the exchange of country-specific knowledge and experiences; but above all, the activities aimed to create a space for students to work together and develop their intercultural competence.

Responding to a need

One of our main motivations for undertaking this project is its potential for making international opportunities at QMUL more inclusive – a key aspect of both the 2030 strategy and the Active Curriculum for Excellence. The current “Year Abroad” programme works very well for some students. However, it is not seen as accessible by many students, particularly students from low-income families who struggle to afford the cost, as well as those, predominantly female, who cannot or prefer not to live away from home for an extended period for various reasons. Virtual exchanges can help to overcome these barriers to international opportunities because there is no cost to the student, and they take place online. In this way, virtual exchanges can advance QMUL’s commitment to equality, diversity and inclusion.

International opportunities are important because they enable students to develop their intercultural competence. This refers to the ability to communicate and cooperate with people from different backgrounds. It is a skill that is highly prized in our globalized economy. Therefore, our project aims to develop intercultural competence among our students. Virtual exchange can contribute to several of Queen Mary's graduate attributes and equip Queen Mary students to become active global citizens. This includes:

- Participate effectively and inclusively in different roles as part of a team, including as a leader

- Collaborate with a diverse range of colleagues

- Engage critically and reflectively with knowledge

- Communicate effectively in a range of formats for different purposes with a diverse range of people

Although this project can help students across the university, it is of particular interest to medical students. Healthcare workers frequently encounter colleagues and patients who have been shaped by diverse values, beliefs and experiences. High levels of intercultural competence can improve quality and outcomes in healthcare. However, because of the intensity and inflexibility of medical school courses, students have limited opportunities to develop their intercultural competence.

The Approach

We designed a five-week virtual exchange based around a simulated pandemic response exercise.

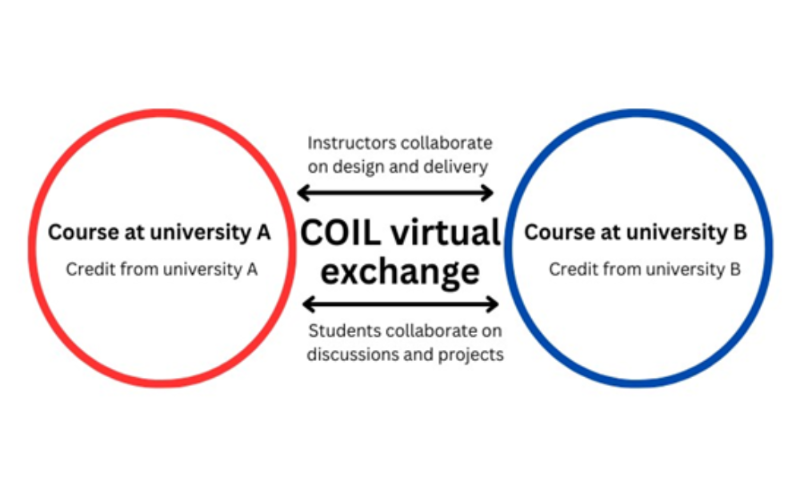

Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) is a specific pedagogical approach to virtual exchanges1. Faculty from two or more cultures work together to develop an exchange programme. Students still follow the curricula at their home universities, and the virtual exchange is designed to complement their existing knowledge - and skill-base. These virtual exchanges can range in length from a few weeks to a semester or longer. Their key characteristic is the emphasis on experiential and collaborative learning activities that encourage students to improve their digital literacy, exchange knowledge, and, above all, develop intercultural competence - that is, the ability to communicate and cooperate with people from different backgrounds.

Simulated pandemic exercises are carefully designed, hypothetical scenarios that mimic the conditions of a disease outbreak. They first emerged as a tool for global health actors to practice their response strategies, identify weaknesses in their plans, and refine their procedures in preparation for the real-life cases. Simulated pandemics have become an increasingly popular tool in public health teaching at Higher Education institutions. Simulated pandemics encourage communication, teamwork and interdisciplinarity; and foster creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving abilities2. Pandemics simulation exercises are, therefore, particularly well suited to the COIL approach, and its emphasis on collaborative activities.

The classes were split into small, mixed groups. Each played the role of a World Health Organization (WHO) Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE). Every week the students were sent a video featuring the (fictional) WHO’s Assistant Director-General for Pandemic Response, who provided an update on the progress of the pandemic and set a collaborative activity with associated deliverables. The activities were designed to achieve COIL objectives outlined above: consolidate the students’ learning in their respective programmes; facilitate the exchange of country-specific knowledge and experiences; and create a space for students to work together and develop their intercultural competence. The exercises were designed to allow students to develop technical skills that may be beneficial in their career, but which are not covered elsewhere in the curriculum.

The tasks included getting students to: explore their own and their peers’ experience of illness and diseases by recording a 'health narrative' on Flipgrid, then watching and commenting on other videos; create photo essays to illustrate social inequalities in their respective locales with commentary on how this might impact the progress of the pandemic; interview each other on the pros and cons of lockdowns as a public health strategy; design posters to increase vaccine uptake in marginalised groups; and perform a PechaKucha – a presentation format comprising 20 slides, each with 20 seconds of commentary – that reflected on their experience of the exchange.

In terms of logistics, we concluded that the best way to deliver our virtual exchange was to meet all students on Zoom once a week. This allowed us to hold plenary sessions at the start of the class, before transitioning into breakout rooms where each SAGE could meet.

Impact

Students were given questionnaires at the start and end of the module. They were asked to what extent they agreed with 19 statements about intercultural, analytical, and scholarly skills (1=not at all; 6=very high degree). The mean scores improved in responses to all 19 statements. Despite a small number of responses (n=16), t-tests demonstrate that improvements for two statements related to intercultural skills are statistically significant at p=.05: for “I understand the forms of verbal and non-verbal communication that exist within different cultures”, the mean score increased from 4.57 to 5.44 (p=.0040); and for “I am aware of how my own cultural rules and biases impact how I view the world and shape my experiences with and view of people from other cultures” from 4.83 to 5.38 (p=.038). These findings align with the broader literature, which shows that virtual exchanges have a measurable impact on intercultural competence3.

However, the qualitative feedback indicates that the UK medical students did not entirely welcome the new approach to learning. Informal discussions indicated that this was related to the widely observed phenomenon that students who are familiar with and comfortable in the traditional classroom tend to be initially resistant towards efforts to introduce new ways of learning4. The reluctance is rooted in fears that the changes will adversely impact students by increasing their workload and making assessments more difficult.

General classroom discussions provide some clues to what was going on. These feelings are likely particularly prominent among medical students. This is partly because they tend to be less exposed to non-traditional pedagogical approaches than students in, say, the humanities and social sciences. In addition, medical students experience higher levels of stress than the general population, so they may be particularly sensitive to change5. This points to the importance of clearly, explicitly and repeatedly explaining to medical students the aims and benefits of the COIL virtual exchange, with a focus on how it will benefit their future studies and careers.

Recommendations

I am keen to encourage and enable colleagues at QMUL to start their own COIL virtual exchanges. I have developed a QMplus module and I would be very happy to talk to colleagues who are interested in designing and delivering COIL virtual exchanges.

QMplus module - How to design and deliver a virtual international exchange

As part of my Queen Mary Academy Fellowship, I created a QMplus module that aims to provide QM staff with the resources necessary to develop and deliver a virtual international exchange based on Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) principles: 'How to design and deliver a virtual international exchange' QMplus: https://qmplus.qmul.ac.uk/course/view.php?id=24196

The first section begins by introducing the main principles of virtual exchanges and the COIL approach; it then explores how COIL virtual exchanges can benefit your students and the module lead. The second section provides succinct, practical advice on: finding a virtual exchange partner; designing a virtual exchange; delivering a virtual exchange; assessing students; and student feedback. The third section provides three case studies of COIL virtual exchanges: a simulated pandemic exercise; one that explores and analyses management issues such as leadership, decision-making and employee problems; and another that focuses on data collection and analysis in scientific research.

Podcast

A podcast in which we discuss our virtual exchange with our collaborator at UC Santa Cruz: https://fulbright.org.uk/our-community/podcasts/

Publications

We have written up our findings and reflections on the work undertaken during the Fellowship:

• One piece has been published already in Medical Education (impact factor=4.9): Jonathan Kennedy et al. (2024). "Improving intercultural competence through a combined virtual exchange and simulated pandemic response exercise." Medical Education 58(5): 646-647 https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.15352

• Another piece had been accepted for publication in The Clinical Teacher (impact factor=1.4). Jonathan Kennedy et al. (forthcoming): How to develop and deliver a virtual exchange based on Collaborative Online International Learning principles (COIL). The Clinical Teacher

• Practice Report to be published in the Journal of Virtual Exchanges. Further details will follow.

References

1Rubin, J. (2017). Embedding collaborative online international learning (COIL) at higher education institutions. Internationalisation of Higher Education, 2, 27-44

2Skryabina, Elena, Gabriel Reedy, Richard Amlôt, Peter Jaye, and Paul Riley. "What is the value of health emergency preparedness exercises? A scoping review study." International journal of disaster risk reduction 21 (2017): 274-283. Rega, Paul P., and Brian N. Fink. "Immersive simulation education: a novel approach to pandemic preparedness and response." Public Health Nursing 31.2 (2014): 167-174

3O’Dowd, Robert, and Melinda Dooly. "Intercultural communicative competence development through telecollaboration and virtual exchange." The Routledge handbook of language and intercultural communication. Routledge, 2020. 361-375. Ismailov, Murod. "Virtual exchanges in an inquiry-based learning environment: Effects on intra-cultural awareness and intercultural communicative competence." Cogent Education8.1 (2021): 1982601

4Dembo, Myron H., and Helena Praks Seli. "Students' Resistance to Change in Learning Strategies Courses." Journal of developmental education 27.3 (2004): 2

5Jordan, Richard K., et al. "Variation of stress levels, burnout, and resilience throughout the academic year in first-year medical students." Plos one 15.10 (2020): e0240667