Widening access to international opportunities: a combined virtual international exchange and simulated pandemic exercise

In collaboration with

- Danielle Thibodeau

We combined a virtual international exchange with a simulated pandemic in which students played the role of advisors to the World Health Organisation (WHO), working in teams to respond to a fictional pandemic. The activities were designed to consolidate the students’ learning in their respective programmes and facilitate the exchange of country-specific knowledge and experiences. The activities aimed to create a space for students to work together and develop their intercultural competence.

Responding to a need

One of our main motivations for undertaking this project is its potential for making international opportunities at QMUL more inclusive – a key aspect of both the 2030 strategy and the Active Curriculum for Excellence. The current “Year Abroad” programme works very well for some students. However, it is not seen as accessible by many students, particularly students from low-income families who struggle to afford the cost, as well as those, predominantly female, who cannot or prefer not to live away from home for an extended period for various reasons. Virtual exchanges can help to overcome these barriers to international opportunities because there is no cost to the student, and they take place online. In this way, virtual exchanges can advance QMUL’s commitment to equality, diversity and inclusion.

International opportunities are important because they enable students to develop their intercultural competence. This refers to the ability to communicate and cooperate with people from different backgrounds. It is a skill that is highly prized in our globalized economy. Therefore, our project aims to develop intercultural competence among our students. Virtual exchange can contribute to several of Queen Mary's graduate attributes and equip Queen Mary students to become active global citizens. This includes:

- Participate effectively and inclusively in different roles as part of a team, including as a leader

- Collaborate with a diverse range of colleagues

- Engage critically and reflectively with knowledge

- Communicate effectively in a range of formats for different purposes with a diverse range of people

Although this project can help students across the university, it is of particular interest to medical students. Healthcare workers frequently encounter colleagues and patients who have been shaped by diverse values, beliefs and experiences. High levels of intercultural competence can improve quality and outcomes in healthcare. However, because of the intensity and inflexibility of medical school courses, students have limited opportunities to develop their intercultural competence.

Approach used

We designed a five-week virtual exchange based around a simulated pandemic response exercise.

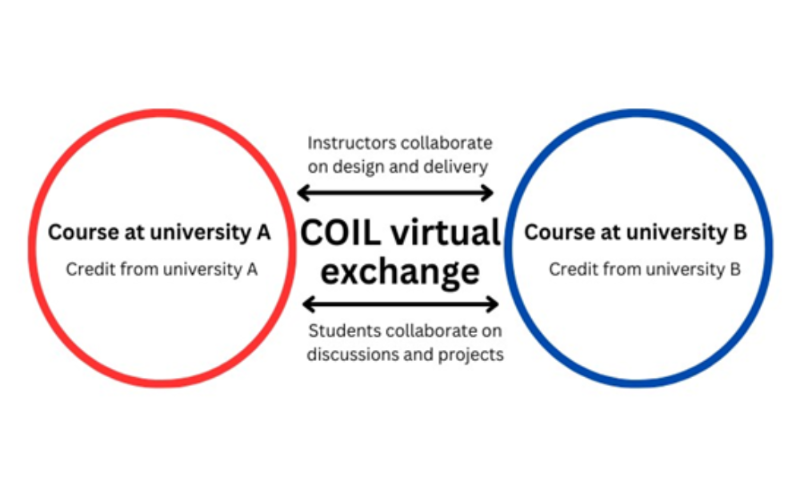

Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) is a specific pedagogical approach to virtual exchanges.1 Faculty from two or more cultures work together to develop an exchange programme. Students still follow the curricula at their home universities, and the virtual exchange is designed to complement their existing knowledge- and skill-base. These virtual exchanges can range in length from a few weeks to a semester or longer. Their key characteristic is the emphasis on experiential and collaborative learning activities that encourage students to improve their digital literacy, exchange knowledge, and, above all, develop intercultural competence – that is, the ability to communicate and cooperate with people from different backgrounds.

Simulated pandemic exercises are carefully designed, hypothetical scenarios that mimic the conditions of a disease outbreak. They first emerged as a tool for global health actors to practice their response strategies, identify weaknesses in their plans, and refine their procedures in preparation for the real-life cases. Simulated pandemics have become an increasingly popular tool in public health teaching at Higher Education institutions. Simulated pandemics encourage communication, teamwork and interdisciplinarity; and foster creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving abilities.2 Pandemics simulation exercises are, therefore, particularly well suited to the COIL approach, and its emphasis on collaborative activities.

The classes were split into small, mixed groups. Each played the role of a World Health Organization (WHO) Strategic Advisory Group of Experts (SAGE). Every week the students were sent a video featuring the (fictional) WHO’s Assistant Director-General for Pandemic Response, who provided an update on the progress of the pandemic and set a collaborative activity with associated deliverables. The activities were designed to achieve COIL objectives outlined above: consolidate the students’ learning in their respective programmes; facilitate the exchange of country-specific knowledge and experiences; and create a space for students to work together and develop their intercultural competence. The exercises were designed to allow students to develop technical skills that may be beneficial in their career, but which are not covered elsewhere in the curriculum.

The tasks included getting students to: explore their own and their peers’ experience of illness and diseases by recording a 'health narrative' on Flipgrid, then watching and commenting on other videos; create photo essays to illustrate social inequalities in their respective locales with commentary on how this might impact the progress of the pandemic; interview each other on the pros and cons of lockdowns as a public health strategy; design posters to increase vaccine uptake in marginalised groups; and perform a PechaKucha – a presentation format comprising 20 slides, each with 20 seconds of commentary – that reflected on their experience of the exchange.

In terms of logistics, we concluded that the best way to deliver our virtual exchange was to meet all students on Zoom once a week. This allowed us to hold plenary sessions at the start of the class, before transitioning into breakout rooms where each SAGE could meet.

Figure 1: A graphical representation of a COIL virtual exchange

Source: Jonathan Kennedy et al. (forthcoming): How to develop and deliver a virtual exchange based on Collaborative Online International Learning principles (COIL). The Clinical Teacher. (Original image.)

Impact

Students were given questionnaires at the start and end of the module. They were asked to what extent they agreed with 19 statements about intercultural, analytical, and scholarly skills (1=not at all; 6=very high degree). The mean scores improved in responses to all 19 statements. Despite a small number of responses (n=16), t-tests demonstrate that improvements for two statements related to intercultural skills are statistically significant at p=.05: for “I understand the forms of verbal and non-verbal communication that exist within different cultures”, the mean score increased from 4.57 to 5.44 (p=.0040); and for “I am aware of how my own cultural rules and biases impact how I view the world and shape my experiences with and view of people from other cultures” from 4.83 to 5.38 (p=.038). These findings align with the broader literature, which shows that virtual exchanges have a measurable impact on intercultural competence.3

However, the qualitative feedback indicates that the UK medical students did not entirely welcome the new approach to learning. Informal discussions indicated that this was related to the widely observed phenomenon that students who are familiar with and comfortable in the traditional classroom tend to be initially resistant towards efforts to introduce new ways of learning.4 The reluctance is rooted in fears that the changes will adversely impact students by increasing their workload and making assessments more difficult.

General classroom discussions provide some clues to what was going on. These feelings are likely particularly prominent among medical students. This is partly because they tend to be less exposed to non-traditional pedagogical approaches than students in, say, the humanities and social sciences. In addition, medical students experience higher levels of stress than the general population, so they may be particularly sensitive to change.5 This points to the importance of clearly, explicitly and repeatedly explaining to medical students the aims and benefits of the COIL virtual exchange, with a focus on how it will benefit their future studies and careers.

Recommendations

I am keen to encourage and enable colleagues at QMUL to start their own COIL virtual exchanges. I have developed a QMplus module – see below for link – and I would be very happy to talk to colleagues who are interested in designing and delivering COIL virtual exchanges.

No such formatter